Listening with the Eyes: The Sense-making of the Father of Neuroscience

Santiago Ramón y Cajals purchased his first microscope in 1877. It was acquired with money he had saved serving as a medical officer in the Spanish army.

Lens-grinding technology evolved greatly in Europe during the 1830s, with a number of lens manufacturers making breakthroughs that were the patented and proprietary manufacturing advances of their era, and by the time Ramón y Cajals, who would become the father of neuroscience, purchased his scope in 1877, the precision of the optics of these lenses was so great that a world, previously invisible because it was too minute to be accessed by the human visual system, could be opened.

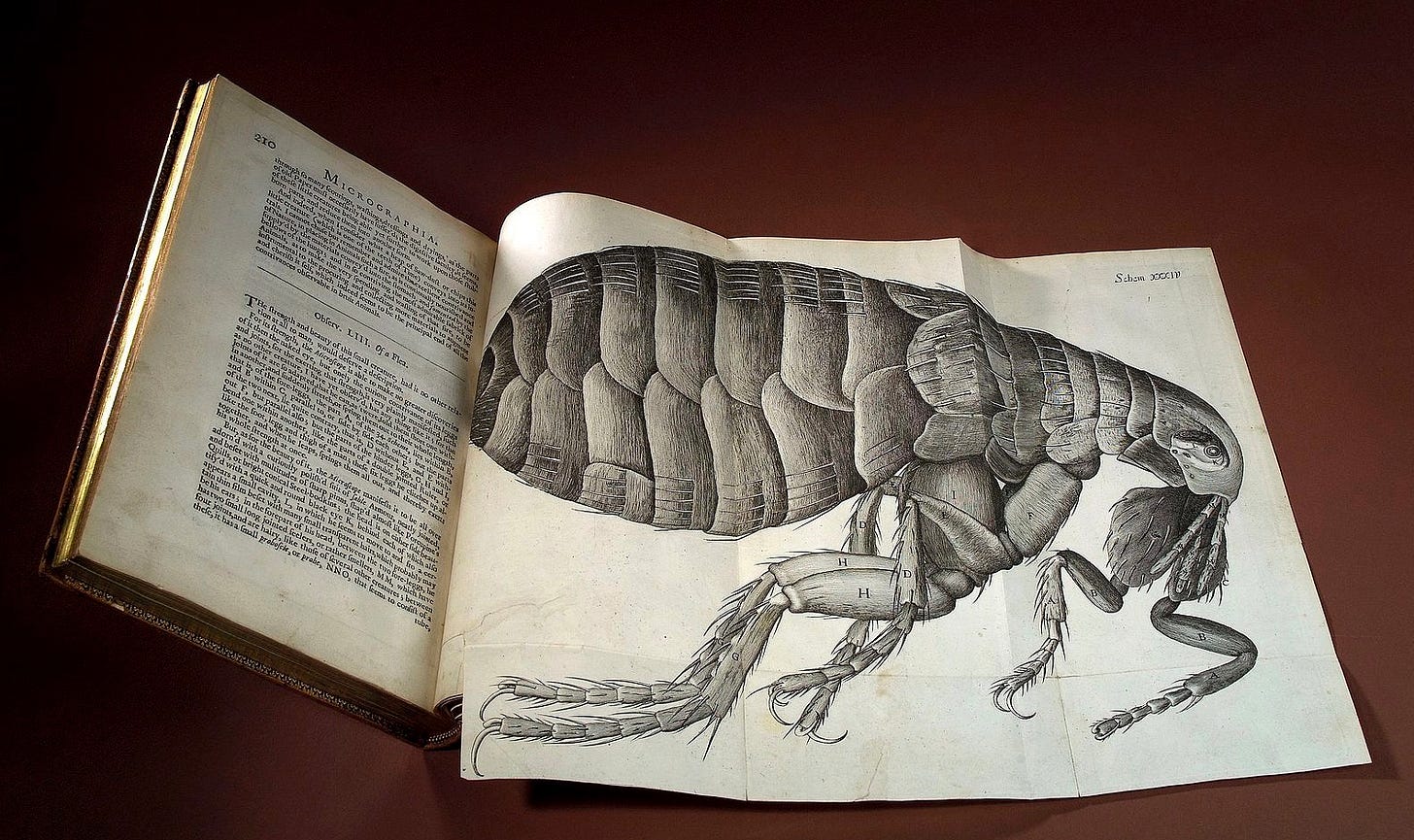

We are, when Ramón y Cajals buys his microscope, one hundred and twelve years forward from Robert Hooke’s first drawings of cork, a hundred years from the dawn of cell theory. (Let’s not forget that it was a theory once.) Beneath the lenses a strange and alien world unveils itself, deeply divergent from the forms we see at visible scale. As this world opens, our minds must expand to encompass these new revelations of the real. Strange creatures step into the field of view, yet they are not chimerical, not fantasies, not fictions. Things we can barely see are magnified into magnificence and horror.

Engraving of a flea, Robert Hooke, Micrographia, 1665.

Think of the microscope as a portal opening on an alien dimension: the strange new world of the tiny. The magnification transports us into another range in the lifescale. Later instrumentation– electron microscopy, eventually particle accelerators–will open to vision successively exponentially more minute worlds: that of the molecule, that of the atom. Yet for now, in the 1870s, we content ourselves with the opening of a new biological frontier. The fundamental unit wholes of life are rendered visible. The cell becomes sensible to us visually. We perceive the building blocks of life: plant cells, animal cells. What a revelation! What glory! What jawdropping beauty in how Nature assembles her symphony of magnificence. Can you not hear the angels singing? These are mysteries heretofore unwitnessed by humans.

Technology extends our senses, amplifies our capabilities. In the case of first the telescope, and then the microscope, what is amplified is our seeing. And we moderns are, to an extent that is ancestrally anomalous, deeply identified with our metaphors of sight. We use the term clairvoyance, with its etymology firmly rooted in vision, to speak of perceptive insight, clear seeing, the ability to penetrate the surface of the real. We talk about really seeing one another. About being seen. Yet this is careless language, in actuality. Merely approximate. What we are really discussing is clear perception. Lucid awareness. It is not sight, but something deeper, more penetrative, more encompassing. Something for which vision is merely a metaphor. And yet, because we love to look, because we identify with the gaze, seeing becomes the metric of our sensing. We substitute the most dear of our five senses for the act of witnessing. Yet note that it could have been otherwise. In a culture that had refined its flavor detection, a culture of great gustatory achievement, we might have used the word clear tasting to denote this deep awareness. Dogs, with a sense of smell ten thousand times more acute than our own, probably call their shamans clear smellers.

My point here is that the application of our sensing onto the world is metaphorical. It is a linguistic approximation. And this points us in the direction of something notable in Cajal’s work, something I will propose to you is deeply strange. Our article begins with the man himself in this thirties, with a microscope, in his lab. It is a selfie from the 1870s, a photo Cajals himself took, having learned photography when the artform was still in its infancy. No iPhone here. No selfie stick. A rudimentary camera, noxious chemistry required to develop the plates. Yet Cajals is undeterred by difficulty. This same man will refine a technique of staining cells developed by the Italian Camillo Golgi to such an extent that it becomes the gold standard, quite literally, for staining neurons. Here he is again, this time in a suit, more at leisure.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Self-portrait, taken by Cajal in his laboratory in Valencia when he was in his early thirties, c. 1885. Cajal Institute (CSIC), Madrid.

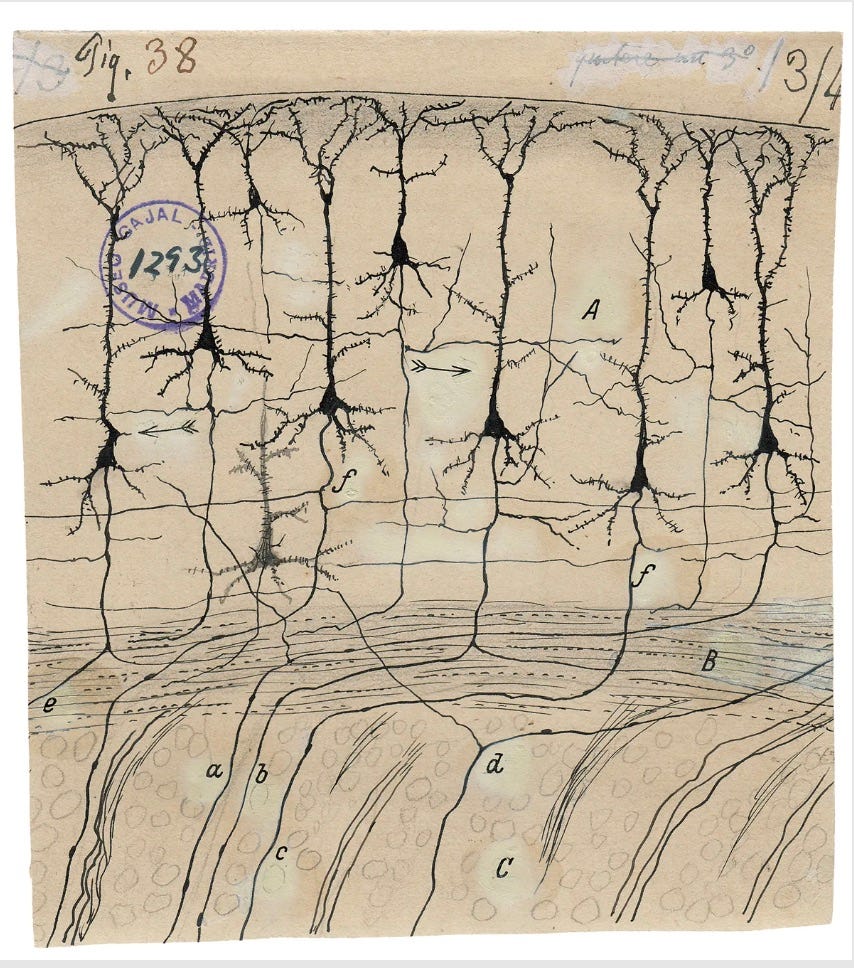

He is an unusual person, this Ramón y Cajals. They will call him a peasant genius, and he will go on to win a Nobel Prize. From a rebellious boy, deeply anti-authoritarian, who is sent to juvenile hall at eleven years old for exploding his neighbor’s gate with a home-made cannon, he will father the discipline of neuroscience, rendering visible, through his microscope, the fundamental cellular unit of neural structure: the neuron. He is the author of the Neuron Theory. A reporter gazing into the cellular depths and documenting his visions in illustrations so startlingly precise they are still used today.

Or so we are told. Or so is the orthodoxy: that he saw the neuron.

And yet I call bullshit on this.

Bullshit, bullshit, bullshit.

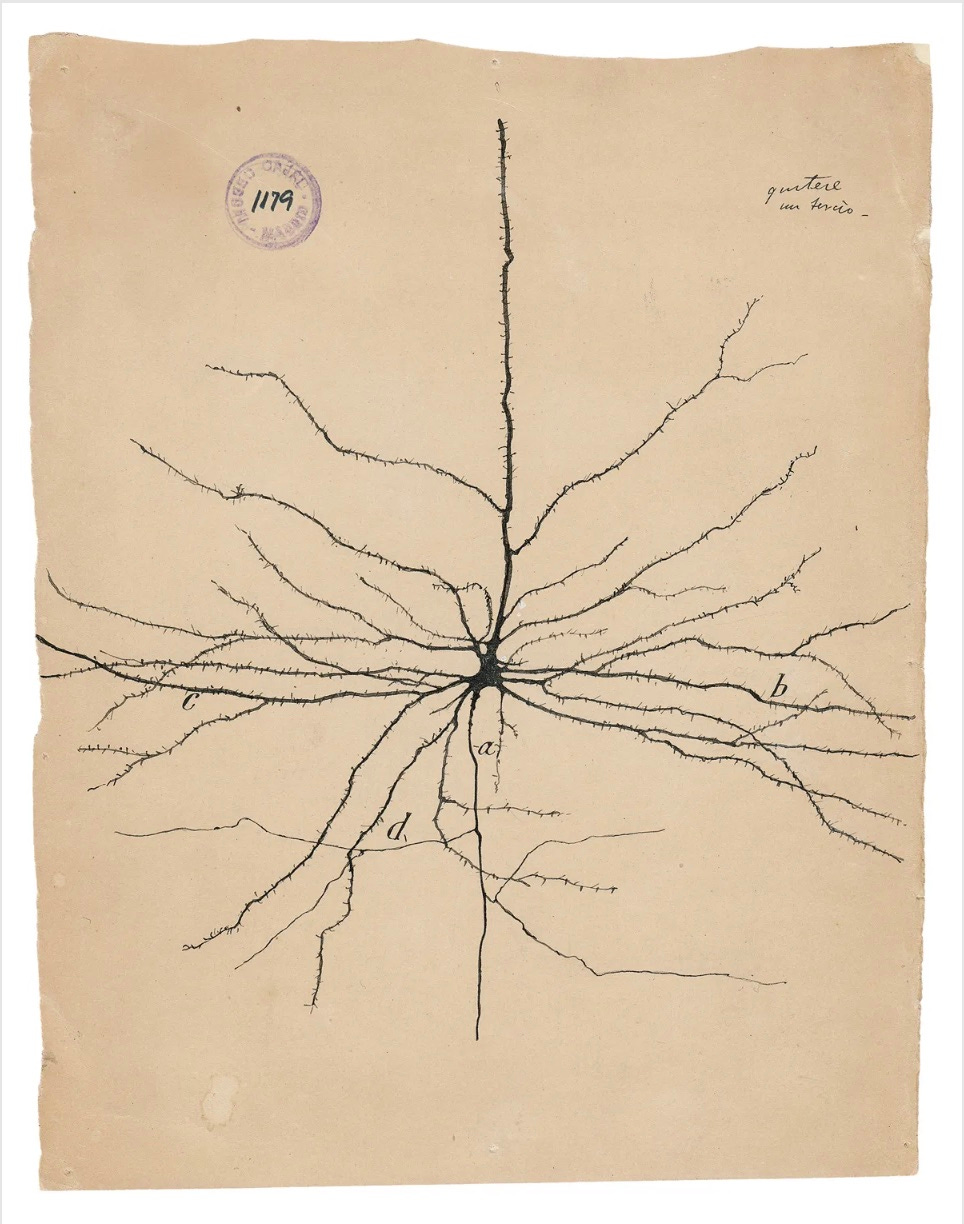

Cajals is an artist. Cajals is an inventor. Cajals is a shaman. He conjures the neuron, the tiny trees that comprise the nervous system, in the image of an inward forest. Cajals invents the texture of the inward landscape of neurology. He doesn’t discover it. He invents it. And he renders it real for us, renders it visible through drawing-as-discovery. Through illustration-as-transmission. Through art-as-revelation. Renders it in such a way that we cannot unsee it, such is its power.

To situate Cajals correctly in the pantheon of disciplinary histories we must add and claim another set of lineages: the artist. Cajals is the cousin of Cézanne, the nephew of Rilke, the brother of Rodin. His medium is not paint, not words, not stone, that is true. His medium is the inward landscape of the body. Yet as Cézanne does not paint still lifes, does not paint mountains, does not paint objects, but subjects, paints not things but the act of seeing them– Cajals is not painting what he saw through the miscroscope but bringing us into his listening through seeing.

Cajals does not see the neuron through his microscope. He is not looking with this eyes, he is listening with them. He says so himself. This is the same man who once blew up his neighbor’s fence. Don’t expect him to do less with your mind.

As he would write in his poetic autobiography, Recollections of my Life,

I finally chose the cautious path of histology, the way of tranquil enjoyments. I knew well that I should never be able to drive through such a narrow path [as microbiology] in a luxurious carriage; but I should feel myself happy in contemplating the captivating spectacle of minute life in my forgotten corner and listening, entranced, from the ocular of the microscope, to the hum of the restless beehive which we all have within us.

Listening, entranced, from the ocular of the microscope. It is such a strange turn of phrase. Because listening is not something we ordinarily do with our eyes. So what does he mean? But you know what he means. Listening is a receptive sense. To listen, again a sort of sloppily-textured metaphor when we apply it beyond the acoustic realm, is to make ourselves available, receptive. Seeing declares. Listening asks. Seeing is a statement, listening is a question. Ordinarily. So to listen with the eyes?

Imagine a man walking through a forest, listening, with a sketchbook. A forest no one has ever seen before, ever visited. A forest in an unknown land. A forest filled with strange and unidentified species of dendrons – this is Greek for trees, don’t you know? It will transmute into dendrites - treelike… Enter into the forest with the man, he is joyful, a bit mischievous, a bit of a disruptor, and he is deeply present. He is paying attention. Look up.

Can you see them, the neurons? The neural structure peeking through the sky? Now take out your sketchbook…

Remember though, that Ramón y Cajals, in this inward forest, listening with the ocular of the microscope extending his listening, is not looking at a three-dimensional forest. In order for the light to pass through the slides, these slices are razor-thin. He is only looking at sections. Only gazing at planes. And so he can only see the slices of trees arrayed upon the plane of the slides. And so he must infer the forest, deduce its dimensional structure, from these fragments. From these potsherds, these shatters of pottery, he must infer the vessels whole and intact. This is what people do not understand. Prior to the neuron doctrine, it was believed that the nervous system was an undifferentiated mass of material. A squiggle. A velvet electrical jelly? The brain a jellyfish encased in skull.

And in this manner his work is an act of construction. A synthesis, an invention. He is a temple builder. He builds the inward world. He sculpts the nervous system. He makes it out of pencil and gouache, conjures it into dimensionality. Evokes it for us.

Details this world like Rodin polishing stone, with the finest penstrokes.

And yet, please recall as well–the staining technique–the chemistry whereby he has rendered this system visible, it is a reductionism. He has disappeared the supporting scaffolding of the circulatory system that always twins the neurology. Deleted fascia, muscle tissue, bone. He has disappeared all of this. In order to help you see the trees, he has disappeared other things. Vanished the soil, let us say, for simplicity. Do not forget that he is a magician. What you are seeing is not the inwardness of the body, but what an artist is showing you. It is something that he created. You are not seeing the intact holism of the body. You are seeing what Ramón y Cajals wants you to see.

I do not believe that Santiago Ramón y Cajals would be pleased about the way the discipline has evolved. I do not believe he would be delighted by the hegemony of rationality, the brain-centric and empirically buttoned-down nature of modern research in the field.

And I will whisper in your ear a secret, something that is going to get under your skin like a splinter, something that is going to get under your worldview, down into the soil of it, the deepest strata, may dislodge something at its roots. Ramón y Cajals was under the sway of an unconscious bias so deep, so unacknowledged, so invisibilized, that it corrupts the entire edifice of his work if we don’t transplant the work in its entirety.

Cajals was under the illusion– the grand illusion of the last five hundred years of the modern world– that I think, therefore I am. Hush, keep this quiet. Finger to the lips. Let us not go around exploding other people’s fences, the retaining walls of modern psyches. Keep this quiet.

He was under the illusion that identity resides in cognition, and that the organ of cognition- the cranial brain- is the sovereign seat of the nervous system. Cajals was a brain supremacist. Hush, don’t tell anyone.

And here I call your attention, one hundred and fortyseven years later, to the utter fallacy of this, and the vast destruction in the wake of this foundation error gaping beneath the edifice of modern neuroscience.

I call your attention to the birth of the autonomic nervous system in the body, to the doors and windows of the house of your nervous system loomed miraculously through the entirety of your living skin. I return the nervous system to your whole body, trace its ethereal lacelines through the entire extension of your inwardness. For in order to feel yourself from inside- and you can do that, can you not?– in order to know yourself through the sixth sense that we call interoception, you most have neurons everywhere. To feel yourself on this three dimensional inwardly volumetric screen, your nervous system must be everywhere. It is the pixels that render this landscape sensible to you. Neurons the tiny bright lights that illuminate with a gut feeling, allow you to sense the curvature of your spine, the tingles in your wrist, the warmth in your heart…

I call the nervous system out of the head, out of the snailshell you were taught to believe it lived in, and back out into the deepest interstices and the fullest extension of your animal, and animate, body. I do nothing other than what Cajals did, listening clearly to the ‘hum of the restless beehive’ that we are.

I repurpose the entire edifice of Cajals now– I claim him, I consume him, I place his entire body of work upon the hearth of the original fire and ignite it. I immolate it in the name of liberation.

Watch the glorious drawings catch fire, go up in flames like tiny ornate cobwebs, immaculate mycelial cabechons buoyed skyward on the flame-lick dark, fireworks all, then watch them re-organize, watch them re-weave themselves upon the loom of the body entire, making you whole.

I kiss you, visionary father of Neuroscience, as the student kisses the Master, and the Master kisses the student, and I make you my own. I claim you & your visionary knowing too. Your method– your epistemological framework, your non-cognitive ways of knowing, your listening through your eyes, your tasting through the hands, your smelling through the ears, your seeing through the sound? This I reclaim as well for all of us interoceptive trackers traveling together in the direction of home.

ENDNOTES, ETC.

Santiago Rámon j Cajal is the Founding father of neuroscience, and the recipient, with Camillo Golgi, of the 1906 Nobel Prize in Medicine for their work on the structure of the nervous system.

A special thank you to Selah Weaver (epistemology), Jimbo Graves (Cézanne, Rilke, Rodin, etc.), Yasuko Sugawara (seeing through sound), Sue Bahnan, Ali Montgomery, Olivia Barber, Shara Raqs, Peter Love, and both sections of my post-doctoral seminar on the new Foundation Model in Autonomics for the conversations that sparked this piece of writing.

Should you be interested, the autumn 2024 LECTURES ON THE NEW FOUNDATION MODEL OF AUTONOMICS are available as a self-paced course here. If you are not interested in having your worldview exploded, you should refrain from watching them. ;)

A book of Santiago Ramón y Cajals staggeringly beautiful drawings is here.

Wonderfully rendered Gabriel. I can feel your hair on fire. Have ordered both of Benjamin erlich’s books and the book of drawings. Please see Jean klein’s book of listening. For me jk was last house on the block. The seeking stopped like a train pulling into a terminal. Open Listening without the listener. All objects dissolving in their single subject. Be, he says, the listening you are.

Beautiful writing.

Busting up old beliefs.

Thank you.

Donna