013 - The Body You Are Wearing

Scientific revolutions often arises from challenge: something inexplicable, something that doesn’t seem to make any sense and yet is true, something which requires us to re-examine our fundamental understandings about how reality works. The origins of the Polyvagal Theory were in a paradox that Dr. Stephen Porges refers to as the ‘vagal paradox’. At the time he formulated the paradox, Dr. Porges was a psychophysiologist running a laboratory studying heart-rate variability in infants, and published a paper in neonatology about the protective features of the Vagus in preterm infants. The Vagus is the 10th cranial nerve, and the primary conduit of the parasympathetic nervous system. Porges’ lab had discovered that a healthy Vagal system was protective to newborn wellbeing, but after publishing the paper received a letter from a neonatologist noting his admiration, but explaining that he had learned in medical school that the Vagus could kill an infant. This ‘killer’ Vagus was a reference to sudden drops in infant heartrate that could be lethal. Porges was left confronted by a paradox: how the same nerve be both protective and lethal? He spent several months with the letter in his briefcase, and then began a deep study of comparative evolutionary neuro-anatomy.

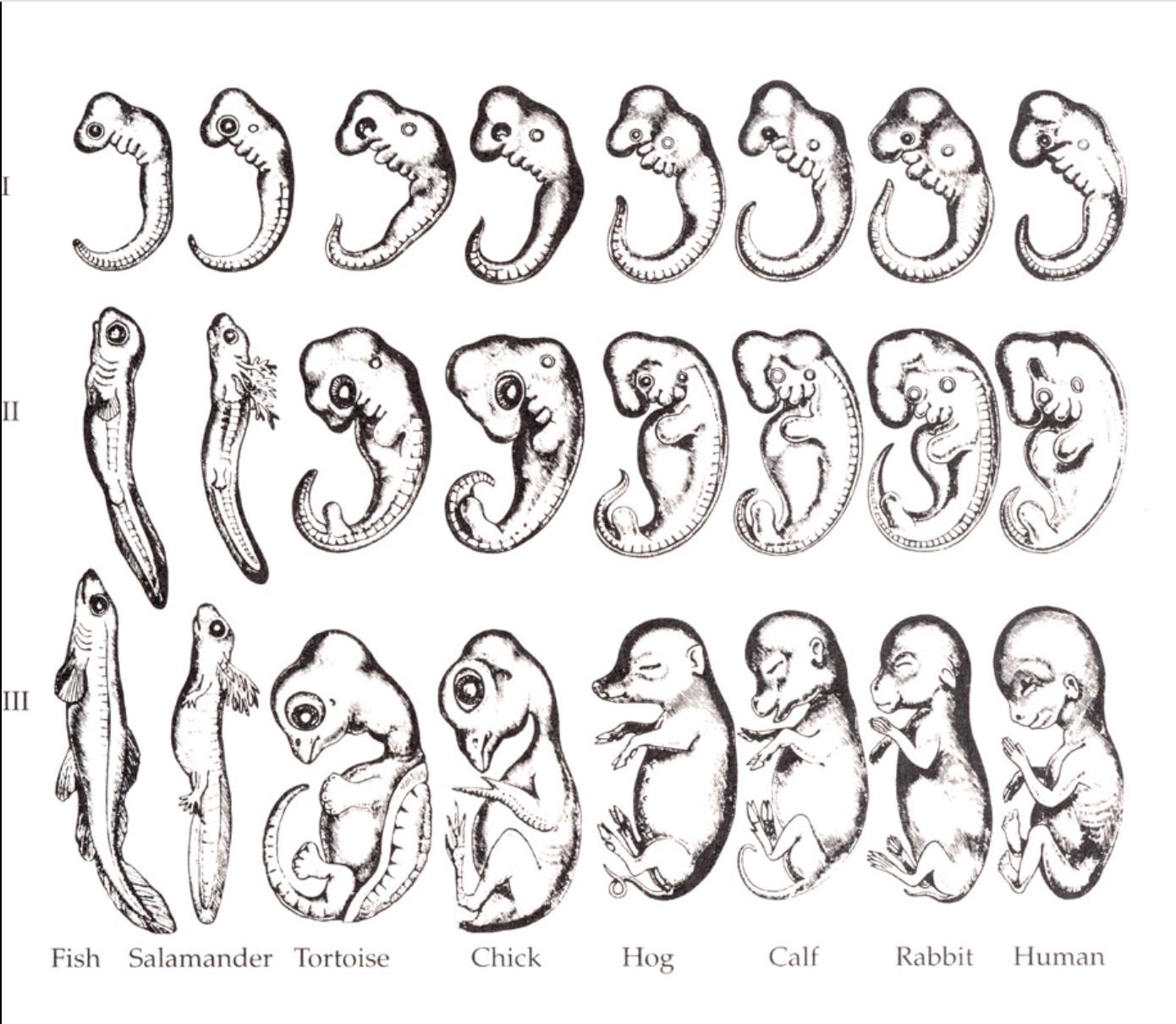

The method by which he eventually arrived at discerning the social engagement physiology or Ventral Vagal Complex, the mammalian neurological system that unites the neural regulation of the face, voice, sucking and swallowing, with the neural regulation of the heart and the lungs into a single functional unit, was based largely on comparative evolutionary neuroanatomy. This is a relevant method of inquiry because ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. An organism’s embryonic development will take it through each of the stages of its evolutionary history. In this way, our evolutionary history and embryonic development can be seen as providing reciprocal windows into one another. The development of an embryo is a window into deep time, and deep time is a window into how we develop.

Somewhere around 200 million years ago, a second (ventral) cardio-inhibitory (heart-slowing) vagal pathway began to differentiate itself from the oldest (dorsal) cardioinhibitory pathway. These evolutionary studies showed a ‘ventral migration’ of a group of cardio-inhibitory (heart-slowing) neurons that moved from their original location in the Dorsal Motor Nucleus (DMX) of the brainstem forward into the Nucleus Ambiguus (NA). Through the long spans of evolutionary time, these ventrally migrating neurons begin to link up, through interneurons, with a set of neurons that innervated the ancient gill arches (the breathing apparatus) of bony fish and that evolved into the neural regulation of aspects of the mammalian face and voice: specifically an anatomically defined and functionally integrated Social Engagement System.1 The Vagus is not a nerve. It is a conduit that holds two distinct systems, both cardio-inhibitory. An ancient unmyelinated system that is primarily sub-diaphragmatic (it originates in the guts) and flows into dorsal areas of the brainstem (the dorsal vagal system), and an evolutionarily more recent myelinated system that innervates the face, voice, and connection systems and flows into ventral areas of the brainstem.

The Social Engagement system is a face/voice complex that unites the neural regulation of the face and voice, synchronizes sucking and swallowing, and integrates the heart and breath. This complex unites the neural regulation of the face, voice, larynx, pharynx, and turning of the head and neck with the heart and breath into a functional unit. It activates to coordinate sucking and swallowing with breathing in a rhythmic pulse. Part of Porges’ certainty that this complex functioned as a neuro-anatomical unit (the face-voice complex) came from the observation that unlike any other voluntary muscles in the newborn, this system is myelinated at birth. This is actually quite strange, because it gives the infant voluntary muscular control over the face, voice, eyes, and middle ear, which seems normal– because it is how we are born– until you recognize that the infant does not have voluntary control over any other skeletal muscle.2

Think about it. A human infant is helpless at birth. It cannot hold its head up, sit, stand, or walk. It is also unable to articulate its interior state to the caregivers on whom it is utterly dependent for survival. And so this system of face (all facial expressions, eye gaze), voice, tuning of the middle ear, uniting with the heart and breath, is the physiological portal whereby the caregiver is able to perceive the interior of the infant. We say that the eyes are the windows to the soul, yet the Face-Voice Complex, we could say, is the doorway to the heart.3

Identifying the Social Engagement System is one of the most significant neurophysiology breakthroughs of the 20th century (another would be identification of the dorsal vagal system). These breakthroughs combined to scaffold the framework of the Polyvagal Theory, which heralded a revolution in our understanding of the human Autonomic Nervous System whose implications, when they are fully understood, will probably reverberate as widely as the paradigm shattering transition from Newtonian to Quantum mechanics. The breakthrough is on that order.

Yet the Face-Voice complex is not the full extent of the Connection System. It is the central aspect of the connection system that is myelinated at birth. Yet your connection system continues to myelinate as you grow. I will make a distinction, going forward, between the Social Engagement system that Porges identified, and the connection system at large.

Why does Polyvagal Theory constrain the connection system to the face/voice complex? In order to understand this, it is necessary to understand the method whereby he arrived at delineating this system, and what its criteria for inclusion were. In order to set the theory on a tenable foundation, because it was assembled across disciplinary boundaries, he had to ground it in both in comparative evolutionary neuroanatomy, and embryonic development. Part of his criteria for inclusion, therefore, was that the system be myelinated at birth, when embryonic development was complete. Yet this gives rise to an unusual problem, another paradox, because humans are not actually neurophysiologically complete when we are born.