Paperback. Version. The. Neurobiology. of. Connection. Finally.

Only at our store. $39 plus shipping.

One of the many ancillary (unasked for) benefits of your subscription to The Neurobiology of Connection substack, is that I’m going to tell you way more than you ever wanted to know about the publishing industry. (Is that really then a benefit, Gabriel, since we didn’t ask for it? you might legitimately wonder.)

The publishing industry is continuing to move through structural upheaval in this age of AI (read my recent post on The Shittification of the Vagus, about all the keyword-oriented AI-generated polyvagal/polivagal/polybagel1 garbage on Amazon.com).

Viewed through a certain lens of empowerment, however, this disruption of traditional publishing is part of a greater democratization of the means of production, of which I am largely in favor. The publishing industry was one of the tightest gate-kept in the world. It ranks right up there with the art world and the music business in defining an in-group and an out-group, determining who gets read and who does not.

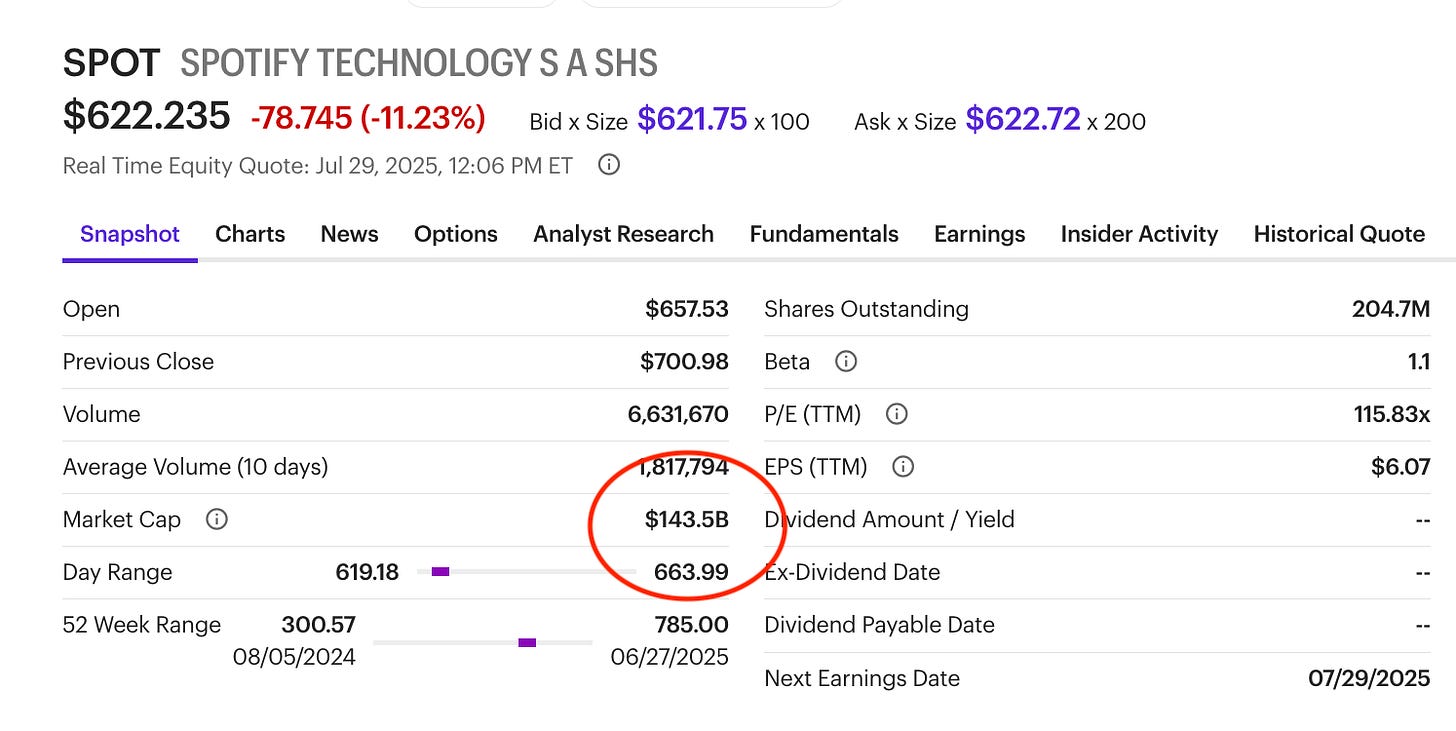

With the advent of Spotify, and other streaming services, the record companies, which were the primary vectors for both exploiting (why Prince changed himself into a symbol, why Taylor Swift bought back her catalog, etc.) and distributing artists, have become increasingly obsolete. Spotify, which is an enormous dumpster fire for musicians, because the royalties are such a pittance, replaced Napster (killed off by the record companies– illegal!) and has effectively stolen everyone’s catalog and is now worth more than all the record companies combined.2

The art world has remained somewhat immune to this kind of structural disruption, if you don’t count NFTs and the entire emergence of digital tokenized art, as far as I can tell, possibly because collecting art is a more rarified enterprise.

With desktop publishing (anyone can learn Adobe InDesign), and print-on-demand (PoD), it is possible for authors with a non-trivial audience to control the unit economics of their publications, which can be a very good idea unless you are at the top of the bestseller lists, because those are the only books in which a traditional publisher will invest in real marketing. This puts financial and distribution power in the hands of the creators, rather than in the hands of mercenary middlemen, financiers, and gatekeepers. Which I like.

Part of the reason Hearth Science didn’t go with a traditional publisher was that in 2021 when we needed to publish Restorative Practices of Wellbeing, it was the analog interface to our learning platform. Because of this, we needed to retain the ability to create new versions of the book, and we wanted to control the visual design such that its branding was tightly linked to our aesthetics. Typically, when you execute a contract with a publishing firm, you turn the design rights over to them. There is usually a clause something like this:

You hand them a manuscript in word format, with a folder of illustrations and diagrams, and they decide how the book looks and feels. And then the contracts say something like this:

Do you realize what this means? Every quote-unquote new book you read was likely finished a year-and-a-half ago. In some cases (e.g., books responding to current events) the turn-around is significantly faster. But most new non-fiction was completed a year or two before you read it. Which means– drumroll– it is not actually all new. Just newly published.

Not that you asked (here we go), but how fast can Jaguar turn a book around, from the time the manuscript is received? We’ve done it in a month. What we publish, sometimes, is so new, so cutting-edge, that it hasn’t even been conceived yet. Sometimes we publish something that hasn’t even been written yet: that’s how fast we are.3 This is, obviously, a competitive advantage in a rapidly evolving field. We can bring something from the lab into your lap in a month. Norton? A year-and-a-half.

At the time, in 2021, as we prepared to put the book out into the world, we hired the inimitable Kevin Barrett Kane, a book designer of great distinction whose dayjob at that time was as the principal book designer for the Stanford University Press. Kevin helped us find a team of editors, including a gifted proof reader. I had already hired several people on the design side of the business to help with posters, so we had both an Art Director and a medical illustrator already in our team. Once Restorative Practices of Wellbeing was completed, we sort of realized that we’d already built a publisher.

Anyhow, to make a long story short, at a certain point we invested in doing an offset printing. This substantively dropped our unit cost per book, and raised the quality of the publication, but we ended up $27,000 out-of-pocket, and with three thousand books that I am still trying to sell. (When we made the decision to go with an offset run, we’d already sold more than 400 copies of the book in paperback. At this point, we’ve sold another 1600 or so hardcover. I still have 1400 of them remaining. This is enough books to fill up pretty good sized room.) Four years later, we are just at the threshold of breaking even on that project. In addition to printing the books, I had hired a publicist, and when all was said and done, we had paid her about $13,000. (Not worth it! Our best magazine placement was one I got myself.) Including book design, the entire project ended up costing us 55 grand. With hindsight being 20/20, we should’ve printed only 1000 copies in the first round (which is what my wife told me to do.). These would have sold out by now, and we could have done a second edition perhaps. While the whole process was expensive, the silver lining I think was the learning. And we carried that forward into future book projects.

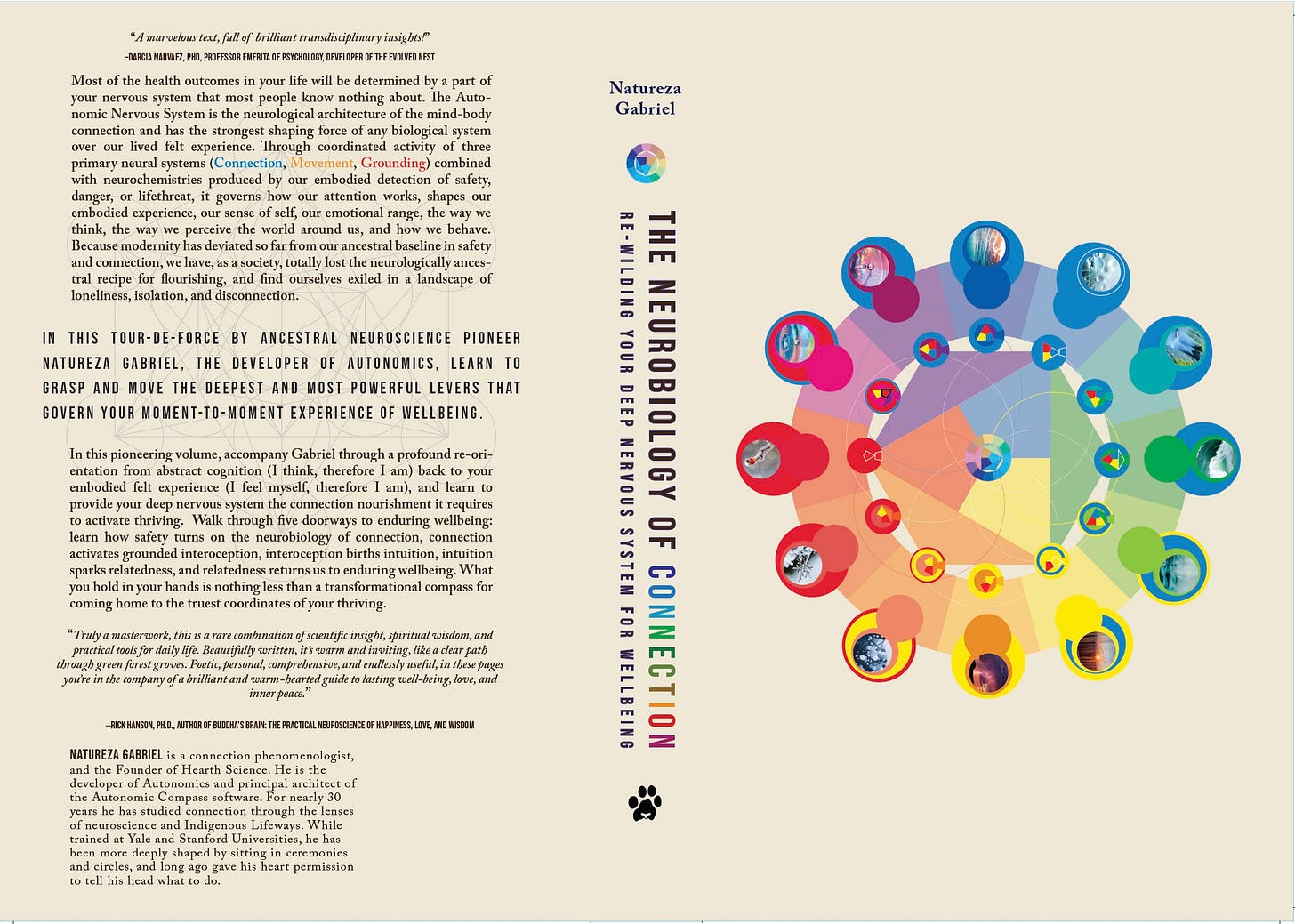

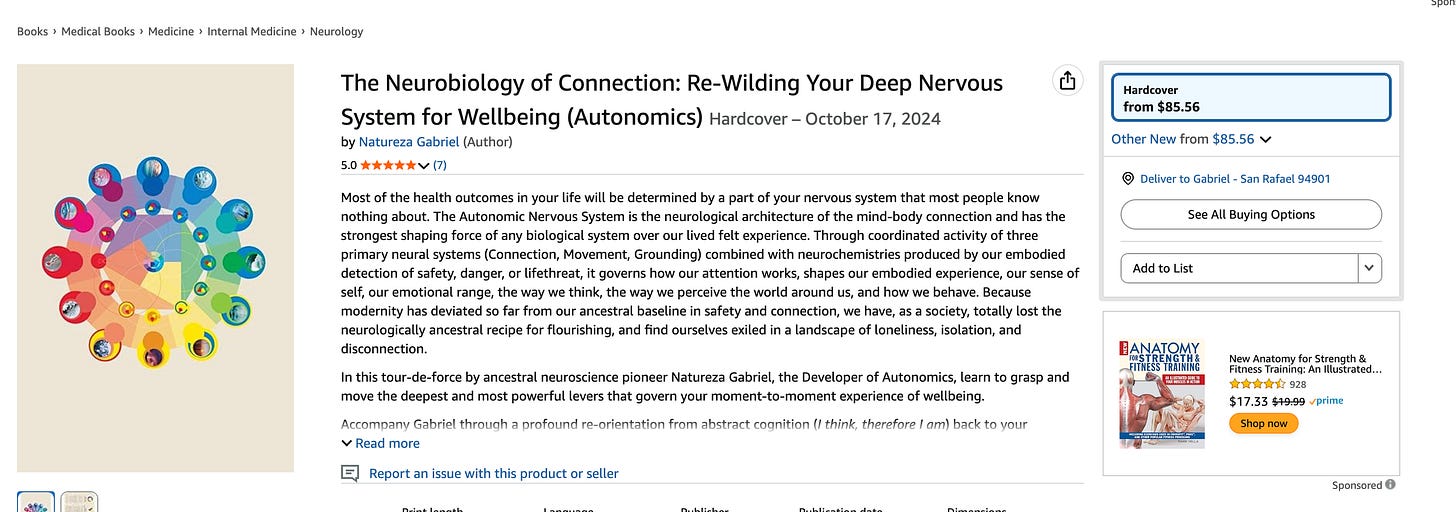

When we printed The Neurobiology of Connection initially, in a hardcover version, we went with a print-on-demand publisher. Because of the length of the book, as well as the fact that it’s in full color, with a case jacket, the printing cost per book was very very high. When we distribute through Ingram, the retailers then take a significant cut. By the time we paid for printing, and the distributors had taken their slice of the pie, the book was already priced at $57, before we made a dime. This is why it has been priced at such an insane price point on Amazon. There were times right after the book came out where it was at $125. As of today, it is $85.56.

Mind you- that is not the price that we set. That is what Amazon’s algorithm has determined they can charge beyond what they are paying us, based on what people have been willing to pay. They are basically getting $27 to distribute the book and another $10 surcharge they just threw in there, because fuck it, they want their siphon as deep into your wallet as they can get it.

But of all of this is to say, as prelude, that we’re finally issuing a paperback version of the text. The paperback is only available on our website. Preorders are open. US orders shipping September 15.

The top 10 wealthiest music labels have a combined market cap of about $95 billion. Spotify has a market cap of $145 billion. Which is to say that Spotify alone is worth more than the top 50 record labels combined.

That was a joke.